Last year, the BBC and Masterpiece Mystery aired a new adaptation of the Sherlock Holmes stories called Sherlock. It’s available now on Netflix Watch Instantly, so if you haven’t seen it yet, go check it out.

But I’m not here to talk about how fantastic the concept and the writing are, or how much I love the performances, or even how anxiously I’m awaiting the next series. I want to argue that the thing that makes this series really groundbreaking is something very subtle: the way director Paul McGuigan handles titles.

In a great recent talk at SVA, Tim Carmody talked about the rise of the “diegetic intertitle” as a form of writing we’ve all learned how to read. The earliest silent movies, uncertain of their ability to convey narrative without words, used titles outside of the diegesis: that is, outside of the world created by the story being told. It was D.W. Griffith who figured out that you could use elements within the story as a sort of titling - letters, newspapers, signage and the like.

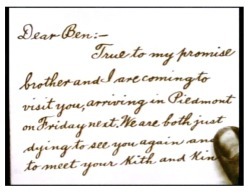

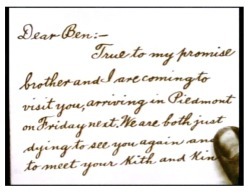

When you see this letter in The Birth of a Nation, you are learning about the visit simultaneously with the characters. The technique allows Griffith to maintain the narrative illusion he’s created, and also gives you, the viewer, a more rich sense of the coming event than you would have gotten from a more traditional title screen.

This way of telling visual stories has worked pretty well for nearly a century, but it’s got its problems. For one thing, it is nowhere near as helpful when the director has to show the text that appears when someone is doing something on a computer screen, or interacting with someone over the Internet. Thus you end up with a long line of movie and TV hackers narrating what they’re doing as they type: gripping drama, right?

The rise of instant messaging, and even more, the SMS, has added another layer of difficulty; I’m convinced that the reason so many TV characters have iPhones is not just that Hollywood thinks they’re cool, but also because the big crisp screen is so darn easy to read. Still, the cut to that little black metal rectangle is a narrative momentum killer. What’s a director trying to make a ripping good adventure yarn to do?

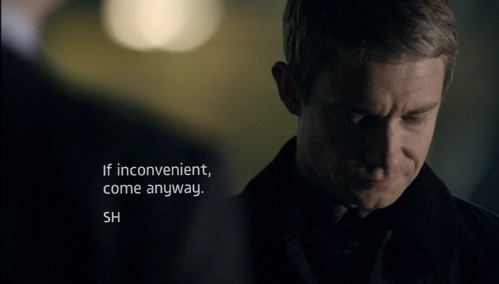

The solution is deceptively simple: instead of cutting to the character’s screen, Sherlock takes over the viewer’s screen.

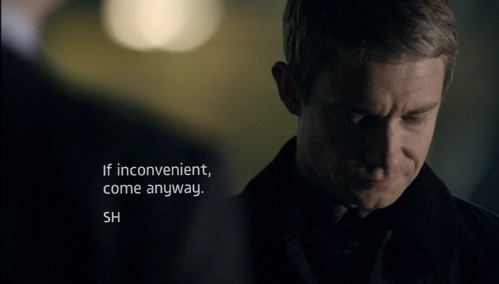

John Watson looks down at his screen, and we see the message he’s reading on our screen as well.

Now, we’re used to seeing extradiegetic text appear on screen with the characters: titles like “Three Years Earlier” or “Lisbon” serve to orient us in a scene. Those titles even can help set the tone of the narrative - think of the snarky humor of the character introduction chyrons on Burn Notice. But this is different: this is capturing the viewer’s screen as part of the narrative itself [1]

It’s a remarkably elegant solution from director Paul McGuigan. And it works because we, the viewing audience, have been trained to understand it by the last several years of service-driven, multi-platform, multi-screen applications.

Last week’s iCloud announcement is just the latest iteration of what can happen when your data is in the cloud and can be accessed by a wide range of smart-enough devices. Your VOIP phone can show caller ID on your TV; your iPod can talk to both your car and your sneakers; Twitter is equally accessible via SMS or a desktop application. It doesn’t matter where or what the screen is, as long as it’s connected to a network device. Entertainment is probably the leading multi-platform use case: as Terri Senft pointed out to me, the Sherlock viewer could very easily be watching this episode on her phone as well. In this technological environment, the visual conceit that Sherlock’s text message could migrate from John Watson’s screen to ours makes complete and utter sense.

I’m also impressed that Sherlock,having established this device, then manages to use it to advance the narrative by telling us something about the character of Sherlock Holmes. We see his words before we ever see him in “A Study In Pink,” the first episode in the series. When he texts the word “Wrong!” to DI Lestrade and all the reporters at Lestrade’s press conference, the technological savvy and the imperiousness of tone tell you most of what you need to know about the character.

The scene also serves to associate Sherlock, right from the beginning, with the technological. True, that’s not a huge leap for a character who describes himself as a “high-functioning sociopath” and who thinks of his brain as his “hard drive.”[2] But the additional underlining of this relationship from our first experiences of the character are important in how we form our impression of the man, and how the series strives to make us all think about Sherlock Holmes as very much our contemporary.

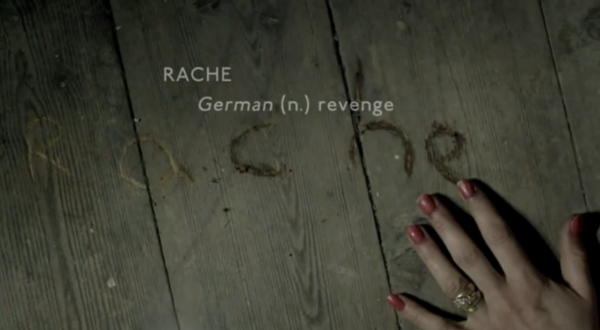

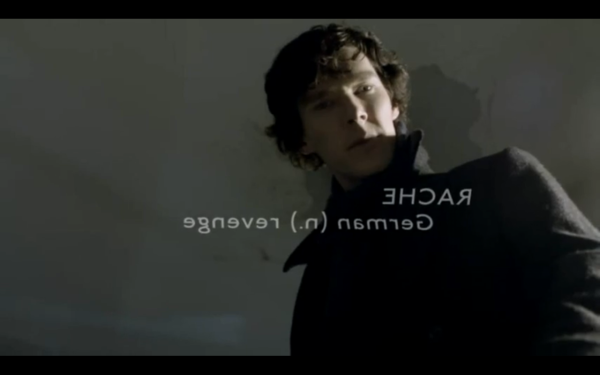

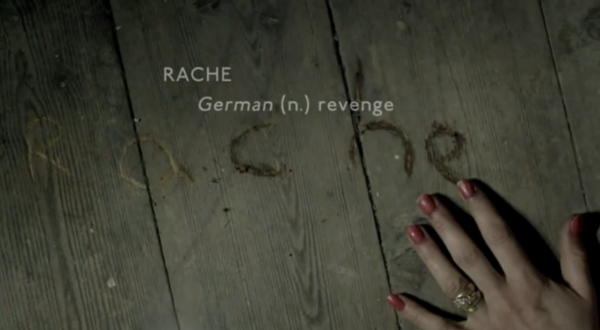

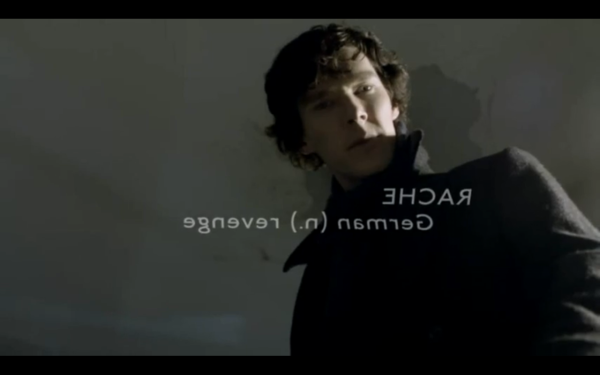

The connection between Sherlock’s intellect and a computer’s becomes more explicit in one of my favorite scenes, later in the episode. Sherlock is called to the scene of the murder from which the episode takes its title.[3] We watch him process the clues from the scene and as he takes them in, that same titling style appears, now employed in a more conventional-seeming expositional mode:

But then the shot reverses, and it’s not quite so conventional after all. The titling isn’t just what Sherlock is understanding, it’s what he’s seeing.

In the same way that text-message titling can take over our screens because whatever we’re watching TV on is just another screen in a multiplatform computing system, this scene tells us that Sherlock views the whole world through the head-up display of his own genius.

This second use of the titling is harder to pull off effectively — in “The Blind Banker,” the only episode of the first season not directed by McGuigan, it turns into a highlight-the-clue device like the one used by Psych. And even episode 3, “The Great Game,” falls back on some “narrate the screen” scenes as Moriarty and Sherlock trade cryptic messages via Sherlock’s website.

But none of that takes away from the achievement, which screenwriter John August calls “the one to beat.” I fully expect the text messaging style McGuigan brought us in Sherlock to become part of the visual narrative vernacular, coming soon to a screen near you.

—————

[1] Another form of screen-claiming worth noting in passing is the aptly-named “violator” - the popup bugs that appear when the network wants to draw your attention to a different show, or whatever’s coming on next. In those cases, it’s the network prioritizing their claim on your screen over the narrative’s - hence, their annoyingness. Thanks to Shana for the vocabulary lesson.

[2] A brilliant updating from the original “lumber room”

[3] Derived from A Study in Scarlet (1887), the first Sherlock Holmes novel.

Special thanks to Tim Carmody for sending me his presentation to revisit while I wrote this piece.

Second, my favorite part is where they chose to put that top-level check-in button: in the middle. Most mobile applications still put the default action at the far left of the screen: that’s where the Twitter iPhone app puts the “new tweet” button, for example. That works great for right-handed users, gripping their phones in their right hands: it’s perfectly positioned for that right-handed thumb. For a left-handed person like me, though, it’s literally a stretch: my thumb has to pull all the way back to the palm to tap. (That’s why I loved the Twitterific iPhone app: it had a left-handed option that reversed the order in which items appeared on the nav bar. When Twitterific dropped that feature, I dropped Twitterific.)

Second, my favorite part is where they chose to put that top-level check-in button: in the middle. Most mobile applications still put the default action at the far left of the screen: that’s where the Twitter iPhone app puts the “new tweet” button, for example. That works great for right-handed users, gripping their phones in their right hands: it’s perfectly positioned for that right-handed thumb. For a left-handed person like me, though, it’s literally a stretch: my thumb has to pull all the way back to the palm to tap. (That’s why I loved the Twitterific iPhone app: it had a left-handed option that reversed the order in which items appeared on the nav bar. When Twitterific dropped that feature, I dropped Twitterific.)